Nothing good:

The Grand Greek Paradox of

the day, meaning the impressive rise in the assets of a nation more

bankrupt than ever, is neither that grand nor that much of a paradox.

There is, indeed, a simple reason that international investors are

piling in to buy some of the nation’s paper assets (e.g. the freshly

minted government bonds and shares in some banks), even though the

country is economically kaput and its government is steeped in long-term insolvency more than ever. What’s this simple reason? The short-term decoupling of the value of paper assets from Greece’s real economy.

Take for instance the new bonds, worth

€3 billion, issued last week. This new debt has been added to the

existing stockpile of €320 billion for a shrinking economy with a

nominal GDP, currently, around €180 billion. To service it next year

alone (in 2015), the government must achieve a gargantuan primary

surplus of 12.5% of GDP and use it all to redeem debt (while Greeks are

in the clasps of untold misery and only 10% of the 1.3 million

unemployed receive any benefits). Why would a self-interested investor

buy these new bonds, in view of the unsustainability of the country’s

overall debt? The answer is, of course, that Berlin and Frankfurt have

signalled to investors that there is nothing to worry about.

Greece’s Grand Decoupling, the Nuclear Option and an Alternative Strategy: A comment on Münchau | Yanis Varoufakis

Tuesday, April 15, 2014

Monday, April 14, 2014

Pay employees to quit

While paying employees to quit may be old news, few and far businesses have practiced this rather adventurous idea. Since we have talked a lot about how to reduce unemployment, I think it may a nice change to talk about how to encourage people to leave a job that is not a good fit for them.

http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/on-leadership/wp/2014/04/14/why-more-companies-should-pay-employees-to-quit/

Gallup has shown that companies that have 9.3 "engaged" employees (those who are emotionally connected with their jobs and willing to go above and beyond) for every one "disengaged" employee saw 147 percent higher earnings per share on average in 2011-2012 when compared with their competitors. Meanwhile, employers with just 2.6 happy workers for every unhappy one saw earnings per share that was 2 percent lower than their competitors. Gallup estimates that "active disengagement" costs the United States $450 billion to $550 billion each year.

But that's not the only reason the idea is something more companies should adopt. For one, it has the potential to improve hiring upfront. If managers have to budget for a $5,000 quitting bonus for employees who don't stick around for the long haul, they might be more careful about truly hiring for fit rather than simply for a warm body. That's particularly the case for high-growth companies such as Zappos or Amazon that are experiencing very rapid expansion.

At the same time, it could also save companies both risk and cost later on. Employers could potentially pay more than $2,000 or $5,000 in severance if they decided to lay off those disengaged workers in the future, rather than motivating them to leave of their own accord. They also risk fewer termination-related lawsuits if more of their workers choose to leave on their own.

Do you think this is a wise approach, at least for fast growing companies? What is the flip-side of it?

http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/on-leadership/wp/2014/04/14/why-more-companies-should-pay-employees-to-quit/

Gallup has shown that companies that have 9.3 "engaged" employees (those who are emotionally connected with their jobs and willing to go above and beyond) for every one "disengaged" employee saw 147 percent higher earnings per share on average in 2011-2012 when compared with their competitors. Meanwhile, employers with just 2.6 happy workers for every unhappy one saw earnings per share that was 2 percent lower than their competitors. Gallup estimates that "active disengagement" costs the United States $450 billion to $550 billion each year.

But that's not the only reason the idea is something more companies should adopt. For one, it has the potential to improve hiring upfront. If managers have to budget for a $5,000 quitting bonus for employees who don't stick around for the long haul, they might be more careful about truly hiring for fit rather than simply for a warm body. That's particularly the case for high-growth companies such as Zappos or Amazon that are experiencing very rapid expansion.

At the same time, it could also save companies both risk and cost later on. Employers could potentially pay more than $2,000 or $5,000 in severance if they decided to lay off those disengaged workers in the future, rather than motivating them to leave of their own accord. They also risk fewer termination-related lawsuits if more of their workers choose to leave on their own.

Do you think this is a wise approach, at least for fast growing companies? What is the flip-side of it?

When Governments Cut Spending

Towards the end of his book, Alan Blinder explores the federal budget deficit so I figured I post a video that answers whether reducing government spending is good for the economy.

Is the professor's opinion biased? Are there examples of spending cuts that led to weaker economic growth in developed economies?

Monetary policy and rich and poor

From Reuters:

For poor nations, the easy monetary

policies in advanced economies are leading to big swings in capital

flows that could destabilize emerging markets. For rich countries, the hoarding of currency by developing nations is blocking progress toward a more stable global economy. Those tensions, which have been brewing for years, seemed to be rising as finance

ministers and central bank chiefs from the Group of 20 economies

gathered last week in Washington, as evidenced by harsh words from

Washington and Delhi...

Both

rich and poor say they are acting in their own self interest, and what

makes the conflict so intractable is that both have very rational

arguments.

Even though the G20

agreed the global economy was on better footing, the tensions suggested

little progress ahead in rebalancing the global economy away from a

state where the rich world borrows massively to buy things from the poor

world.

"This is not a healthy place," Raghuram Rajan, governor of India's central bank, told a panel ahead of the G20 meeting.

At an earlier meeting, Rajan was criticized by Bernanke, former Fed chief, for his position. At the same meeting:

Charles Evans, president of the Chicago Federal Reserve was also

critical of Rajan's position. "We try to pay attention to the effect

that those economies have on our economy and the effect we have on

theirs, but at some point our mandate, our responsibilities, are for the

U.S."

Much of the tension could be eliminated if fiscal policy were part of the toolbox. True or false?

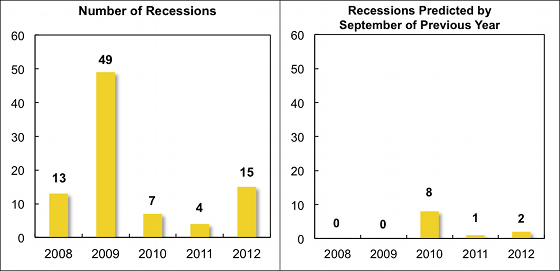

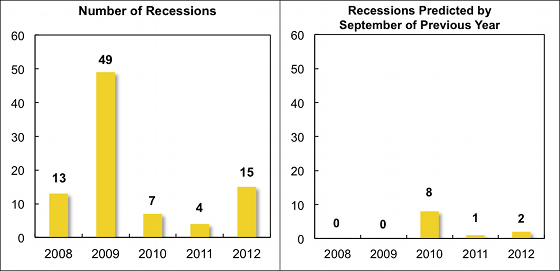

How well do economists predict turning points? |

Blinder says that he and and a few other economists predicted the Great Recession of 2008. It all depends on what it means to predict. From a summary of a recent IMF study:

The panel on the right shows the number of cases in which forecasters

predicted a fall in real GDP by September of the preceding year. These

predictions come from Consensus Forecasts, which provides for

each country the real GDP forecasts of a number of prominent economic

analysts and reports the individual forecasts as well as simple

statistics such as the mean (the consensus).

As shown above, none of the 62 recessions in 2008–09 was predicted as

the previous year was drawing to a close. However, once the full

realisation of the magnitude and breadth of the Great Recession became

known, forecasters did predict by September 2009 that eight countries

would be in recession in 2010, which turned out to be the right call in

three of these cases. But the recessions in 2011–12 again came largely

as a surprise to forecasters.

“There will be growth in the spring”: How well do economists predict turning points? | naked capitalism

The panel on the right shows the number of cases in which forecasters

predicted a fall in real GDP by September of the preceding year. These

predictions come from Consensus Forecasts, which provides for

each country the real GDP forecasts of a number of prominent economic

analysts and reports the individual forecasts as well as simple

statistics such as the mean (the consensus).

As shown above, none of the 62 recessions in 2008–09 was predicted as

the previous year was drawing to a close. However, once the full

realisation of the magnitude and breadth of the Great Recession became

known, forecasters did predict by September 2009 that eight countries

would be in recession in 2010, which turned out to be the right call in

three of these cases. But the recessions in 2011–12 again came largely

as a surprise to forecasters.

“There will be growth in the spring”: How well do economists predict turning points? | naked capitalism

Financial services, not just for the wealthy!

Financial advising has traditionally been exclusive to wealthy people. However, more and more start-ups today have realized that there's an underserved customer segment that is not rich and want some "hand-holding" in terms of financial planning. This reminds me of Walmart, which slowly occupied retailing in small towns where people did not have easy access to department stores and where there wasn't much competition. Targeting an underserved population may turn into a huge business.

What do you think about this business model? Would it revolutionize financial advising?

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/04/12/your-money/start-ups-offer-financial-advice-to-people-who-arent-rich.html?ref=business&_r=0

Saturday, April 12, 2014

NYT: Executive Pay: Invasion of the Supersalaries

Just as timely for a discussion of pay gap between executives and minimum-wage workers.

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/04/13/business/executive-pay-invasion-of-the-supersalaries.html?ref=business&_r=0

This is a short excerpt:

The current system of executive compensation, with its emphasis on performance, can theoretically constrain pay, but in practice it has not stopped companies from paying their top executives more and more. The median compensation of a chief executive in 2013 was $13.9 million, up 9 percent from 2012, according the Equilar 100 C.E.O. Pay Study, conducted for The New York Times. The 100 C.E.O.s in the survey took home a combined $1.5 billion last year, a slight rise from 2012. And the pay-for-performance metrics — particularly the idea of paying executives with stock to align their interests with shareholders — may even have amplified that trend. In some ways, the corporate meritocrat has become a new class of aristocrat.

Economists have long known that high executive pay has contributed to the widening gap between the very rich and everyone else. But the role of executive compensation may be far larger than previously realized. In “Capital in the 21st Century,” (Belknap Press), a new best seller that is the talk of economics circles, Thomas Piketty of the Paris School of Economics makes a staggering observation. His numbers show that two-thirds of the increase in American income inequality over the last four decades can be attributed to a steep rise in wages among the highest earners in society. This, of course, means people like the C.E.O.s in the Equilar survey, but also includes a broader class of highly paid executives. Mr. Piketty calls them “supermanagers” earning “supersalaries.” “The system is pretty much out of control in many ways,” he said in an interview.

It continues:

In 2010, as part of the Dodd-Frank Act, Congress passed a rule that requires public companies to disclose the ratio of the C.E.O.’s pay to the median compensation at the firm. The main objective was to give shareholders a yardstick for comparing pay practices across companies, said Senator Robert Menendez, Democrat of New Jersey, who sponsored the provision.

But he acknowledged that the ratio could serve another function. “Productivity can’t come from the person at the top of the pyramid alone,” Mr. Menendez said. “You want a well-compensated work force to bring productivity and the execution to improve the bottom line.”

She suggested an alternative ratio that would compare the chief executive’s pay to the federal minimum wage, a number that would not cost companies anything to calculate. It could also serve another function: She proposes eliminating any tax deductibility for executive compensation that is more than 100 times the minimum wage. “It is simple and sweet,” she said.

Do you think the publishing pay ratio has work thus far?

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/04/13/business/executive-pay-invasion-of-the-supersalaries.html?ref=business&_r=0

This is a short excerpt:

The current system of executive compensation, with its emphasis on performance, can theoretically constrain pay, but in practice it has not stopped companies from paying their top executives more and more. The median compensation of a chief executive in 2013 was $13.9 million, up 9 percent from 2012, according the Equilar 100 C.E.O. Pay Study, conducted for The New York Times. The 100 C.E.O.s in the survey took home a combined $1.5 billion last year, a slight rise from 2012. And the pay-for-performance metrics — particularly the idea of paying executives with stock to align their interests with shareholders — may even have amplified that trend. In some ways, the corporate meritocrat has become a new class of aristocrat.

Economists have long known that high executive pay has contributed to the widening gap between the very rich and everyone else. But the role of executive compensation may be far larger than previously realized. In “Capital in the 21st Century,” (Belknap Press), a new best seller that is the talk of economics circles, Thomas Piketty of the Paris School of Economics makes a staggering observation. His numbers show that two-thirds of the increase in American income inequality over the last four decades can be attributed to a steep rise in wages among the highest earners in society. This, of course, means people like the C.E.O.s in the Equilar survey, but also includes a broader class of highly paid executives. Mr. Piketty calls them “supermanagers” earning “supersalaries.” “The system is pretty much out of control in many ways,” he said in an interview.

It continues:

In 2010, as part of the Dodd-Frank Act, Congress passed a rule that requires public companies to disclose the ratio of the C.E.O.’s pay to the median compensation at the firm. The main objective was to give shareholders a yardstick for comparing pay practices across companies, said Senator Robert Menendez, Democrat of New Jersey, who sponsored the provision.

But he acknowledged that the ratio could serve another function. “Productivity can’t come from the person at the top of the pyramid alone,” Mr. Menendez said. “You want a well-compensated work force to bring productivity and the execution to improve the bottom line.”

She suggested an alternative ratio that would compare the chief executive’s pay to the federal minimum wage, a number that would not cost companies anything to calculate. It could also serve another function: She proposes eliminating any tax deductibility for executive compensation that is more than 100 times the minimum wage. “It is simple and sweet,” she said.

Do you think the publishing pay ratio has work thus far?

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)